tv Moyers Company PBS March 23, 2013 5:00am-6:00am PDT

5:00 am

♪ this week on "moyers & company" -- >> they confuse bank profitable with bank safety and soundness. they're not the same things. there's a right way and a wrong way. and your questions for richard wolf. >> professor wolf. >> professor wolf. >> we'll answer the question. funding is provided by carnegie corporation of new york, celebrating 100 years of the fiphilanthropy. the coleberg foundation with support from the partridge foundation. the clements foundation, park foundation, dedicated to heightening public awareness of critical issues. the herb alpert foundation, supporting organizations whose mission is to promote passion

5:01 am

and creativity in our society. the bernard and audrey rappaport foundation. and gummowitz. the betsy and jesse fink foundation. and by our sole corporate sponsor, mutual of america, designing customized, individual, and group retirement products. that's why we're your retirement company. welcome to the question of the week. are the banks, banks too big to fail and too big to jail, are these monsters courting another disaster? that's what it looks like. as you no doubt heard last week, the senate permanent subcommittee on investigations issued a report an hauled in key executives from jpmorgan chase, the world's biggest derivative

5:02 am

trader, demanding to know how the bank blew $6.2 billion in funny money. i mean, derivatives, and hid the losses with some fancy accounting tricks aimed at fooling both regulators and the public. senator carl evan, the chairman, bluntly summed up what they found. quote, it exposes a derivatives trading culture at jpmorgan that piled on risk, hid losses, disregarded risk limits, manipulated risk models, dodged oversight, and misinformed the public. the trail that directed the jpmorgan celebrated silverhead chairman and ceo jamie dimon, said to be barack obama's favorite banker, an e-mail requesting an increase in the bank's risk taking received a two-word reply from dimon. i approve. but the well-connected dimon, whose bank was being bailed out by almost $25 billion from taxpayers even as he was making

5:03 am

$35 million a year, was spared from testifying personally and having to dispose exactly what he knew about the shenanigans of his lieutenants and when he knew it. among the many of us who will be anxiously awaiting those revelations, should they come, is my guest sheila bear, a long-time republican. she was appointed the head of the fdic. during the financial collapse, she oversaw the takeover of more than 300 banks that went belly up and was an outspoken opponent of the taxpayer bailouts. as one influential observer wrote during that time, sheila bear never forgot her most important constituency isn't the thousands of banks she regulates but the millions of americans who use them. she now has the systemic risk council, an independent committee formed by the pugh charitable trust to monitor what's being done to prevent another financial collapse. she was at this table a few

5:04 am

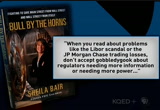

months ago to talk about her book "bull by the horns: fighting to save main street from wall street and wall street from itself." i'm please the to welcome you back. >> thank you. >> i thought perhaps we were getting the bull by the horns until i saw those hearings last week. >> yeah, it really was amazing. a lot we knew already, but it was really laid out in gruesome detail in that report. it was quite shocking. you know, i don't think -- i think the system has incrementally safer, a little safer, but nothing like the dramatic reforms we really need to see to tame these large banks and give us a stable financial system that supports the real economy, not just trading profits of a large financial institution. >> were you surprised by anything you heard at those hearings? >> i was. i viewed i, like a lot of peopl jpmorgan chase as a free will managed bank. i was surprised at them to build these huge positions and even

5:05 am

when he started calling foul, the next level of management above him really didn't get on top of it. i was not surprised by appalled by the way they were manipulating their models that are supposed to be able to determine how much risk is involved in various trading positions. >> what advantage did they gain from manipulating those positions? >> well, there were a couple things going on. one was it was clear they were trying to boost their regulatory capital ratios in anticipation of new capital rules coming into effect. this is a key defect with the way regulators bank. regulators view capital adequacy at these large banks. they left those capital ratios to be determined in part by the risk models of the banks. the banks produce models that say these assets are safer. that means they can report a higher capital ratio. it really gives them upside down incentives to manipulate the models. >> for the layman, what is the capital ratio? >> a capital ratio is simply the percentage of your assets, what's on your balance sheet, the percentage of that funded

5:06 am

with common equity. when banks have a low capital level, that means they're borrowing a lot to support themselves. whether it's a household or a big bank, you borrow too much and you don't have enough common equity to absorb losses, that's what it means to fail. you start having losses, you don't expect them, you have a very thin capital base, you can't make good on your debt obligations, you fail. >> this is what happened in the buildup to the big crunch. >> exactly. >> what surprised me is they could hide these hundreds of millions of dollars in losses that you say and survive even internal scrutiny. >> yes, and even after it was in the wall street journal, you know -- >> hiding in plain sight. >> yeah, i think what was going on was they were in this big power game with a bunch of hedge funds who realized this london oil trader was building up positions in a narrowly traded product. they were trying to squeeze them. they let the public know, jpmorgan chase has exposed you. then the losses really started

5:07 am

to mount. it's amazing the papers picked up on it before most senior managers or the regulators. >> where were the regulators? >> i don't know. i think we need a culture change with the regulators. i talk about this a lot in my book. you've got a lot of good-will intentioned people, but they confuse bank profitability with bank safety and soundness. they're not the same thing. there's the right way and there's a wrong way to make money. they're almost aligning themselves to bank managers and wanting to have the appearance of profitability because they think that makes a sound banking system. it's really upside down. you can't ignore the problems here. some of that is overlooked. >> we thought we were going to get a culture change after the big crash. >> yeah, well, i think it's coming slowly but not fast enough. it's amazing that, you know, so many years after the crisis less than half of the dodd frank rules have been completed. a lot of them are watered down. >> by? >> well, the regulators have

5:08 am

come to do this. some of the provisions in dodd frank had too many provisions, but we get more exceptions when these proposals come out such as the volcker rule. we get these rules that are hard to enforce and easy to game. >> when dodd frank and the volcker rule managed to get through a recalcitrant congress, many of us were hopeful. would you tell us briefly what dodd frank was supposed to do and what's happened to it and what the volcker rule was supposed to do and what's happened to it? >> dodd frank is a very large -- it is a complicated law. probably more complicated than i would have preferred, but it is what it is. at the heart of it is ending too big to fail, giving the government new tools to resolve large financial institutions when they feel in a way it will not hurt taxpayers and not subject them to risk. well, it forced losses on the shareholders and creditors of the large financial

5:09 am

institutions, which is where they belong. it also requires the federal reserve board to have much tougher prudential standards, so higher capital, more stable liquidity, less reliance on short-term debt. those are the types of things that were problems during the crisis and the fed has been mandated to have better regulation to prevent banks from getting in trouble to begin with. the volcker rule, too, a key part, it was designed to prohibit proprietary trading by those institutions in the government safety net. if you're a bank holding company that has an insured bank that has fdic-backed deposits or access to the federal reserves discount window, you have a lot of government support provided to traditional banks. so volcker is really about customer service. your banking model should be serving customers, making loans. if you're facilitating trading, make your money out of a commission and not by trying to make a profit off the spread.

5:10 am

that's really what volcker was about. it turned into a lot more complicated thing than it should have been. i talk a little bit about structural changes that i think could give us a more robust regulatory system because now i think we have cognitive capture, which means -- >> what does that mean? >> it means the regulators tend to look at the world through the eyes of the banks. they don't look at themselves as independent of the banks. their charter is not to protect the public but to protect the banks. this is the premise of the bailout. if you take care of the banks, you'll take care of the broader economy. it doesn't turn to out that way. >> i took your book on a trip last week. i was reading the last chapter again in anticipation of your comi coming. you say when you read about problems like the libor scan dl or the jpmorgan chase trading losses, don't accept gobbledygook about regulators needing more information or needing more power.

5:11 am

the next day i look at the hearing and more gobbledygook. >> well, you know, they had the information. there were plenty of warning flags. examiners should have been all over this. it really was remarkable how lackadaisical things were until the losses were there in front of them. then it was all hands on deck, but it was too late at that point. >> this is what's scary to me. the senate found not only did the regulators fail to act aggressively in uncovering the risk r but that dimon on his own for a period of time decided not to comply with federal regulations and flatly denied the regulators' crucial data. does that scare you? >> right. well, that was amazing and was troubling in that -- to the extent it reflects how he views examiners and their role. he was apparently worried about leaks, but, you know, i think most examiners are quite, you know, confidentiality is sacred

5:12 am

with examiners. i wouldn't worry about leaks. i don't think that was a legitimate concern or one that was justified. >> could reckless behavior like this bring the system down again? >> it was a very big loss but, you know, i think it underscores how even banks that are viewed as very well managed how there can be major management breakdowns and how these derivatives can generate very, very large losses in a very short period of time, how volatile they are. so i think this is all problematic and should inform some future regulatory choices. one is on the volcker rule. another is on bank capital. the next time, that $6 billion could be $16 billion. the capital rules are all upside down. they need to be fixed. and the volcker rule needs to be fixed. >> do they need to be fixed or used? i thought both dodd frank and volcker had pretty well put into place the tools that regulators need. >> well, i think they do too. you know, the statute could have

5:13 am

been more prescriptive. instead, it delegated authority to the regulators to fix it, and the regulators wanted it that way. the fed and treasury didn't want a lot of prescriptive rules in the statute itself. they wanted the authority to do it themselves. they got what they wanted, but the record has not been as good as it should be. the volcker rule is still not finalized. what's been proposed is very weak. it needs to be strengthened. what's been put out there is pretty weak. >> so for the stranger who came to me in the dallas airport where i was reading this book and looked at it and said, you know, i don't understand it. i don't even know why i should care. >> yeah, he should care, or she. >> why? >> well, look, when this crisis hit, first of all, there were a lot of bad loans made by large institutions that should have known better. were there borrowers that took advantage of it? yeah. but there were a lot of innocent victims as well. it wasn't just the mortgages. when all those losses came home to roost with financial

5:14 am

institutions that did not have enough capital to absorb those losses, what did they have to do? they had to pull back on the credit lines. they had to pull back on lending. people, small businesses, couldn't get their credit lines renewed or couldn't get their -- a lot of homeowners couldn't get their mortgages refinanced. you know, people who are in the middle of development projects had their money pulled. there was a huge pullback in credit because thee large financial institutions had too much leverage, and they had to pull in their horns and nurse their balance sheet. you had these large financial institutions with huge trading operations that could be subject to volatile losses, not enough capital absorbed them. you get into another recession. >> is the banking system safer today? >> yes, it is. there is more capital in the system now. that's been done through the stress testing process that the federal reserve board has led. and that has helped. that has helped a lot. we do have more capital, more of these banks balance sheets being funded with common equity and

5:15 am

less with debt. but the ratios are still far too low. i think people can understand that basic notion. if you get capital levels up, you reduce the leverage. that makes the system much more resilient. they're better than prescriptive rules too. we never know what the next stupid thing is going to be that's going to get a bank into trouble. >> we human beings are brilliant. >> exactly. if they have a nice cushion of capital, whatever that next stupid thing is, they're going to have a much better chance of surviving it and continuing to lend to the economy than if they have very thin capital levels, which means they have a lot of leverage, a lot of our money. >> are these big banks still too big? >> well, i think they are. it's more complexity than size. most of the losses during the crisis, those were occurring in the trading operations, not the lending parts of these banks. the loans, they immediate some bad loans, but we probably could have handled the losses on the loans. even a very big bank, if it takes deposits and makes loans,

5:16 am

i think we can deal with that. the fdic has been dealing with that kind of business model for a long time. when loans get into trouble, generally it's a slower process. you have time to work with the borrower, try to mitigate losses, but with a trading loss, it's immediate, and you're really in the soup if it's unexpected. >> give me a quick definition of the libor scandal. >> the libor, the london inner bank offered rate, was a process that was easy to gain. it was basically a survey to a bunch of large banks that said, if you had to borrow today, what do you think the interest rate would be that you'd have to pay? so they were allowed to guess, right. they didn't have to base it on actual transactions. so the libor, the traders at these large institutions figured out if they could manipulate the rate, if they colluded and gave information together that would raise or lower the rate, they could make money. so it was just good, old-fashioned manipulation of an

5:17 am

interest rate that's very important to a lot of municipalities and corporations that used interest rates to manage interest rate risk as well as people who have mortgages and credit cards. >> so it could impact all of? >> it absolutely could. there's nothing more say sacred than an interest rate to the financial institution. if you're manipulating that rate, you got a problem with your financial system. the thing that frustrates me about libor, this was criminal manipulate. there's no doubt about it. you read the e-mails of these guys colluding with one another. i think only two traders at ubs have been charged. nobody has gone to jail yet on it. the settlements that have occurred are forcing the corporations, the corporate entities of the banks to pay these huge fines, but individuals are being prosecuted or brought to justice. i don't understand that. >> our attorney general and

5:18 am

other officials say, well, we can't really prosecute them because they're too big. they would hurt related companies -- >> i mean, honestly, look. if prosecuting the individual is going to -- i mean, even if you accept the premise of too big to fail, which i don't accept, you can still sue the individuals. that's not going to bring the system down. >> so what's going on? >> the financial regulatory enforcement system, it's basically become a cost of doing business, right. so you bring these cases, you settle them, it's paid out of the corporate pocketbook. individuals aren't held accountable. very few people have gone to jail. you don't change behaviors. the whole point of this is change behavior. we're just not doing it. >> i read the other day that between 2009 and 2012 jpmorgan chase, jamie dimon's bank, paid $16 billion for legal defense fees and $8 billion in settlement for cases involving regulatory avoidance.

5:19 am

i mean, that's almost a third of their profits. if i were a shareholder, i'd say why are you spending all that money? >> it's amazing that the easiest way to avoid all this is to stop doing it, change these behaviors. mary jo white will be the new s.e.c. chairman. she's got a long history in law enforcement. she was in the private sector for many years. that's created some controversy. >> defending big banks. >> i'm going to hope with her. i think she's at the end of her career. her legacy is going to be how well she does at the s.e.c. someone like her can be the very best regulator because they know all the bodies are buried. she's not trying to cultivate a client list to go back into practice. this is the last thing she's going to be doing. but i hope she looks at the s.e.c. enforcement strategy and starts suing individuals and looks at it as a way to change behavior not just a way to rack up press releases. i think that fresh look is going to be helpful.

5:20 am

let's all wish her luck. >> there are proposals floating around congress to break up these last remaining big banks. are you sympathetic toward them? >> i am, though i think government is not doing much of anything these days. i never know -- these large financial institutions still have a lot of clout on the hill. reopening dodd frank and trying to get congress to do something on this, i think it's a very healthy discussion. at the end of the day, i'm not sure where it will take us. my focus has been, and the focus of the systemic risk council, has been on the regulatory tools that are already on the table with dodd frank to deal with this problem. the fed and the fdic have the authority to order a restructuring of these large banks or divestiture if they can't show they can be resolved in a way that doesn't hurt the rest of the system. if they fail, they can go into a government-controlled bankruptcy or a traditional bankruptcy and not impose losses on anybody else. that's an important showing that they have to make. if they can't make it -- but then the fdic have now joined

5:21 am

authority to say, well, you need to get smaller, restructure so it can resolve you in a way that won't hurt the rest of the system. >> they also have armies of lobbyists, these big banks, that came after you when you were at fdic. >> they still do. >> now that you're running the systemic risk council. describe how that lobbying and that culture of washington works. >> it is not good. you know, i think the lobbyists view their success rate by how much good stuff they can get for their clients, right. their clients want to make money. their focus is regulatory changes that will make money for their clients, not to promote system stability. i'm not saying, you know, listen to everybody, sure, but understand when those lobbyists come in, whether you're a regulator or member of congress, they're arguing their own bottom line. they're advancing positions that are going to make them more profitable and making them more profitable is not members of

5:22 am

congress' job. there needs to be more separation. people need to rise up and say, i'm sick of this. i'm going to start voting -- my vote about you is going to determine whether i think you're on top of financial reform, whether you're standing up to these big banks not whether you're coddling them. >> i went back to your final chapter where you said we need to reclaim our government and demand that public officials, be they in congress, the administration, the regulatory community, act in the public interest, even if reforms mean lost profits for financial players who write big campaign checks. that's a marvelous aspiration, but in practice? >> i think members of congress need to rise above. look, i know they're under tremendous pressure to raise money, get re-elected. why are they there to begin with if they don't want to do the public service? do what's right and let the chips fall where they may.

5:23 am

you and i have talked nostalgically about the 1980s when we had the world war ii generation and leadership ranks in congress especially in the senate. they did rise above a lot of the special interests with tax reform and fixing the social security system. they managed to survive re-election. if you take principled positions, stand up for them, explain them to your constituents, you know, maybe they'll raise more money by refusing the wall street guys and going to the main street constituents who vote for them. i think at the end of the day they'll sleep better at night t too. >> that's all the more reason to read "bull by the horns." sheila bear, thank you very much for what you're doing and for being with me today. >> thanks for having me. ♪ it's not only our banking

5:24 am

system that remains questionable and shaky, it's the whole of our economy, that complex mix master of capital and labor, prices and production, goods and services, rewards and punishments, largely driven by private decisions in what has been defined, mythologically, as "the free market." capitalism t, it turns out, is a capital idea if you have the capital. which brings us back to richard wolf. i say "back" because as many of you will recall, this provocative and imaginative economist was here just about a month ago to lay out, in his words, how "capitalism has hit the fan." here's the centerpiece of his argument -- >> for the majority of people, capitalism is not delivering the goods. it is delivering, arguably, the bads. and so we have this disparity getting wider and wider between those for whom capitalism continues to deliver the goods by all means, but a growing majority in this society which

5:25 am

isn't getting the benefit, is in fact, facing harder and harder times. and that's what provokes some of us to begin to say it's a systemic problem. >> my conversation with richard wolff opened such a world of ideas that on the spot i asked him to return, and i asked you to send us the questions you'd like to put to him. your response was as overwhelming as it was smart and informed. just take a look at some of the letters we printed out from our website, billmoyers.com. thanks to everyone who wrote. we'll get to some of these in just a minute, and to even more of them with richard wolff in a live chat next tuesday at our website, billmoyers.com. richard wolff taught economics for 35 years at the university of massachusetts and is now a visiting professor at the new school university here in new york city teaching a special course on the economic meltdown. his books include "democracy at work: a cure for capitalism" and "capitalism hits the fan: the

5:26 am

global economic meltdown and what to do about it." welcome back, richard. >> thank you, bill. >> let's move on to questions from the viewers who tuned into our conversation three weeks ago, hundreds of them responded. here's michael from tulsa, oklahoma. >> professor wolff, what can we as individuals in communities do to regain control of our economic destiny? >> we have an old tradition in the united states of doing things in a cooperative way. we celebrate it with phrases like team spirit or team effort. it's the idea that a project will be better done if everybody has an equal stake and an equal say in the decisions that will determine the outcome. i like that idea, i believe it has a lot to do with our commitment to democracy. so my answer to the question is we ought to have much more democratic enterprise. we ought to have stores, factories and offices in which all the people who have to live

5:27 am

with the results of what happens to that enterprise participate in deciding how it works. >> that's the subject of your book, "democracy at work: a cure for capitalism." and we will come back to it in a few minutes. here is jose from naples, florida, and kristin from joplin, missouri. >> professor wolff. on the last show you mentioned how you were against regulation. i agree with you on the most part that regulation has been a failure. what would be your alternative to regulation? >> without regulation how do we respond to widening economic disparity in our society? >> you said last time you were skeptical about regulation because the regulated found ways to evade, overcome or negate it. >> yes, skepticism is the politest way i know how to say this. i think that we have now learned in our society that regulating big corporations and regulating wealthy folks is an exercise in futility. it'll work for a while, but

5:28 am

those folks have the incentive and the resources to work around it, to evade them. >> the hearings last week. jpmorgan -- >> morgan, yeah. >> chase continuing to -- >> stunning. >> take these risks. >> stunning. it's as if the whole meltdown of 2008 and '09 hadn't happened, as if all the risk-taking can continue and all the massaging of the internal rules of the banks can be manipulated, all of that. it seems to me we've learned the lesson that regulation is usually coming too late after, in a sense, the disaster has happened. and then it is evaded and avoided and watered down. it doesn't work. and we have to learn the lesson. so i would respond by saying, we have to make a more basic change. instead of constantly coming too late to the regulation activity let's change the way decisions are made so we don't have to be constantly after people regulating them in this kind of sad effort that never quite succeeds. let's change the basic

5:29 am

decisions. >> i thought glass-steagall worked fairly well from the time it was enacted in the depression with roosevelt to 1999 when bill clinton and congress repealed it. >> well, i don't want to get into a dispute with you, bill. i think -- >> go right ahead, everybody else does. >> i think there was a long history of evasion. in other words ways were found in the '60s and '70s long before the repeal, ways were found by banks setting up investment banks, setting up new financial institutions to get around if not the letter then certainly the intent of that kind of regulation. when it was found possible politically first to weaken glass-steagall and then eventually to repeal it, well, that was even better. but basically the minute the regulation was set the regulated industries took it as a problem to be solved. then they hired the economists like me, the accountants, the lawyers and all the other specialists to figure out how to

5:30 am

get around it. >> and armies of lobbyists, let's face it. >> armies of lobbyists to make sure that the laws get massaged and the rules get adjusted so that they can get around it. that's why we keep having financial scandal after financial scandal, hearings after hearings. after a while when you keep doing this you realize that even if you get some benefit, and i see your point, from a regulation for a while, it's only a matter of time. and now that the corporations have gotten really good at getting around it the time for them has been reduced and so we're back to the question isn't there a better way than letting them do their thing and coming late to the table with another regulation? >> okay, here's martha from natick, massachusetts. >> i see a perfect storm coming. capitalism is predicated on unlimited growth, but we live in a finite environment and we seem to have a dysfunctional democracy unable to resolve that contradiction. how do you see climate change

5:31 am

and our diminishing natural resources such as fossil fuels and water impacting this crisis in capitalism? >> capitalism is a system geared up to doing three things on the part of business: get more profits, grow your company and get a larger market share. those are the driving bottom line issues. corporations are successful or not if they succeed in getting these objectives met. that's what their boards of directors are chosen to do, that's what their shareholders expect. that's the way the system works. if along the way they have to sacrifice either the well-being of their workers or the well-being of the planet or the environmental conditions, they may feel very bad about it, and i know plenty of them who do. but they have no choice. and they will explain if they're honest that that's the way this system works. so we have despoiled our environment in a classic way. that's why we have huge cleanup

5:32 am

funds, that why we have so many problems. that's why we have to impose all kinds of costs on companies now to deal with this problem. so i'm not very hopeful. i don't think this is a system that has a place in it for us to seriously deal with the limits to growth, with the need to preserve our environment, to take care of our health as a people because we have a system that pushes forward with a kind of intensity that pushes those issues to the side. >> janet from woolwich, maine. >> if you could be president with a cooperative congress, what are the three most critical things you would do to ensure that we have a healthy economy that is sustainable, particularly in light of a growing aging population? thank you. >> i would pick the following number one, solve the unemployment problem. in a sense

5:33 am

it's the most urgent one we have. if the private sector -- and here i'm paraphrasing franklin roosevelt in the '30s. if the private sector either cannot or will not provide the work for millions of americans who want the work, then it's the job of the government to do it because no one else is. and if i were president, i would follow roosevelt and immediately create and fill millions, millions -- i'm talking 15 to 20 million jobs in the united states right away. number two, i would make it would some have called a "green new deal," that is the major thing these people would be doing would be to deal with the environmental crisis that we have, to change the way we use energy. for example ,just to give one, to give us the proper mass transportation system that advanced countries in other parts of the world already have that we ought to have. millions of people could go to work producing that system and give us a way to move our goods and move our people around the society using less oil and gas with less damage of injury and death the way our car-driven

5:34 am

system has, with less pollution of our environment. here's a way to benefit people on many scales while we put to work those who want to work with the raw materials and tools that are available. and the third thing i would do is take a page from italy, yes, italy who passed a law in 1985 called the marcora law which said the following wonderful thing. if you want employment you have a choice in italy. you don't just have to collect your weekly unemployment check the way we do here in the united states, you have an option. if you get together with ten other unemployed workers and you agree to do the following thing, the government will give you three years of your unemployment payments upfront, right now, in a lump sum. what you have to agree to is that together with at least ten other people you're going to start your own cooperative business which you all together work. the feeling in italy was if you give people a chance to own and operate their own business

5:35 am

collectively they'll be more committed to it, more invested in it, more likely to make a go of it than simply collecting a check. and meanwhile they'll be producing things and they'll feel better about themselves. and they'll have a more productive role in the community. if you give everybody a vested interest in their enterprise, they work harder, they work better, because it's theirs. they're not just working for the man, they're working for themselves, which is a dream americans have had, way back from the beginning. sixty years ago the united states was less unequal than the capitalisms in europe. now we are more unequal. so yes, it is possible to have capitalism with a much more human face than the ones we have here in the united states and in britain particularly where we have allowed things to go in a very different direction. >> but isn't italy in a mess today? we all know about the euro crisis. those governments are in trouble, austerity's being imposed throughout the mediterranean area. we had this explosion with

5:36 am

cyprus -- explosion of fear with cyprus being bailed out and the depositors in the banks having to contribute to the cost of bailing out. a tiny island threatens to bring the euro system down again. >> absolutely, and that cyprus story is extremely important. even though it's a very small country and people might not pay attention because it is small. here is the austerity program of raising taxes and cutting government spending, taking a qualitative new step to help bail out a capitalism that hasn't worked in europe and that has crippled this little country of cyprus. the step taken to try to fix the problem is to literally reach into the private, insured bank accounts of people in the local banks in cyprus and take money out of it to pay for fixing this broken system. for all working people, and not just in europe, here in the united states, too, this should be a wakeup call if you still need one that we're in a

5:37 am

situation where the most dire, unexpected, unimaginable steps are being taken to fix a system that keeps resisting being fixed so that we are required now to dip into people's checking accounts and literally take the money away. >> richard, one of our viewers, antonia murrero asks, "student loan debts are overwhelming me and many others. what does professor wolff think would happen to the economy if those debts could be forgiven in personal bankruptcy? is that even possible? >> well, the law in the united states specifically prevents you from using bankruptcy to erase your student loans. bankruptcy does allow you to erase other kinds of debts if you can't pay them. but the student loan system was set up to prevent that. so students are in a very specially bad place by virtue of this. we've never before done this. in our history as a nation we've never before required college students to take anything remotely like this level of

5:38 am

debt. we're still -- we're requiring students to accumulate huge amounts of debt to get bachelor's degree, let alone more advanced degrees, at the same time that we offer the graduates the poorest job market and prospects in a generation. that's a one-two punch. you have to borrow more than you can afford to face a job which will not allow you to ever pay it off, hence this person's very intelligent question. how is this going to work? we've solved a problem in our society, how to educate the next generation. and let me tell you, this is an important matter. we economists believe that the single most important factor shaping the future of any economy in the world including the united states is the quality and the quantity of the educated trained labor force it produces. college and universities are where we do that. if we're crippling an entire generation with debts they

5:39 am

cannot support and jobs that will not encourage them to continue in their studies we are as a nation shooting ourselves in the foot going forward. it's a demonstration of the dysfunctionality of our system. and then the question comes could we forgive the students' debts? well, it's an interesting idea. but how then do you go to the people who can't afford their credit card debts or their home debts or their mortgage debts -- they're all hurting. and the students have a special claim, i give them that. and we need those students, i understand it. but we have to go at the root of a society which allows unspeakable wealth to accumulate in the hands of a tiny minority while condemning an entire generation of students to a set of burdens. we don't want them to have those burdens. we need what they can produce for us as a society. >> but what does this young woman do who says she's overwhelmed by her debt? >> many students are not aware that they actually have some

5:40 am

ways to help them, but the more broad answer i would give you is you need a social movement. if there were masses of students saying, "this is intolerable," and saying it loudly and saying it publicly, peacefully for sure, but making it clear, then the powers that be would begin to realize that there are millions of students, upward of 15, 16 million people go to colleges and universities in the united states. you're talking about a very well educated constituency. if they were organized and mobilized you would begin to get the response of dealing with their crises much more effectively than what we have now. >> here's a synopsis, richard, of a lot of similar questions that bring us to your book, "democracy at work: a cure for capitalism." a viewer who identifies himself as a longtime fan of dr. wolff writes, "you're passionate about workers' self-directed enterprises. can you explain briefly why you think these are the way to save capitalism? critics say your alternative may

5:41 am

work in theory but not in practice." >> my point is that workers ought to be -- all of us who work in an office, a factory or a store-ought to be in the position of participating in the decisions governing that enterprise. and i do that not only because i believe in democracy. and let me say that if you do believe in democracy, it's always been a mystery to me why that democracy that you believe in doesn't apply to the place where you work. after all, five out of seven days of every week, most of your adult life, you're at work. so if democracy's an important value it ought to be at your job because that's where you are most of the time. and democracy at the job means the following. if you have to live with the decisions that are made in a job, what you're producing, what technology's being used, what the health conditions of your workplace are, what's done with the fruits of your labor, literally whether your factor or

5:42 am

your office continues, since you have to live with those decisions you ought to participate, the basic idea of democracy. so i like the idea of cooperative enterprises because it fulfills my value commitment to democracy. whereas a capitalist enterprise doesn't because it keeps all the decision making in a tiny minority. we all who go to work have to live with their decisions, but we don't articipate in them, not even to speak of the community that has to live with the decisions. but the second reason is i see concrete results coming from an enterprise that was run by the workers collectively, and let me give you a few examples. first, most of us believe that if the workers themselves made a decision that they would close the enterprise and move it to china, i don't think so. i think that the whole running away of enterprises out of the united states was made possible because the decisions to close enterprises here and to open them in another part of the

5:43 am

world where you could get away with paying workers much less was a decision that was very good for the folks who make the decisions, but not for the average workers there. so if we had decision making made by the workers in place they wouldn't undo their own jobs and they wouldn't move. and that would make a very different economic system from the one we have today. second example, suppose a technology was being considered by the corporate heads who make the decision, the board of directors, and it was one that wasn't safe, it created too much noise, too much air pollution, despoiled the water, hatever. if it's a bottom line decision of the typical sort the board of directors and the shareholders seeing profit using that technology might go ahead and use it because it's profitable and that's what they're called upon to do, make profits. if the workers collectively made the decision knowing that they had to breathe that air, they had to hear that noise, they had to live with that water and so did their spouses and their children and their neighbors, i bet you you'd get a different decision because they would

5:44 am

weigh the costs and benefits of that decision differently. and my third example, although i could give you many, bill, if you want them. the third example, when it comes to deciding what to do with the profits, suppose instead the workers themselves made that decision democratically, how do we divide the profits? you think they would give a handful of top officials wild sums of money to buy $40 million apartments on fifth avenue while everybody else was having to borrow money to get their kids through school? i don't think so. i think that people collectively would distribute the wealth more to some than others for all kinds of reasons, but they would do it in a much less unequal way than we have in a capitalist system. so i challenge all of those who are concerned with a more equal system, with less inequality, to come up with a better way of achieving it than having workers be in a position to make the decisions as to how we divide the profits because that is the single most important

5:45 am

determinant of the inequality of income in our society. >> but how do you answer this viewer? "in 1994 when united airlines was on the brink of financial collapse a deal was made creating the biggest employee-owned company in the u.s. in 2002 the airline filed for bankruptcy. >> my answer is the following and it's very important. for workers to own something is one thing. for workers to become the directors of their own enterprise is something else. worker ownership means for example, and we have lots of examples both in the united states and around the world, that the workers become in a sense shareholders. they are the technical owners. but if the workers who become owners, and i'm not against that, but if the workers who become owners don't change the way the enterprise is operated it remains a capitalist enterprise. it still has a board of directors, a handful of people who make all the decisions. it's true that the workers may

5:46 am

vote for who those people are, but they've left the structure of the enterprise in the old form, hierarchical, top-down. that's what was done in united airlines. i was involved in that. i actually know. >> how so? >> they called me in at a couple points to participate in some of the discussions, the international association of machinists, which was the union that was part of that. so they left the old capitalist structure, they weren't willing to go beyond say, we the workers become owners, but we leave the running of the enterprise, the directing of it, the day-to-day decisions in the old form made by the old experts. part of a movement away from capitalism to a cooperative enterprise requires that the people of the united states stop believing that the folks at the top have some magical entitlement to give them that position. >> i think most of them have, if journalism and the social science surveys are reporting what's actually going on out there.

5:47 am

>> yeah, and i think that there has to be a change. i think most americans have to recognize that the folks who run our enterprises, they had to learn how to do that. and we can all learn how to do that. it's the old argument in a sense that comes out of our history. >> here's a viewer named jeff chiming in. "dr. wolff, can you please give a concrete, not academic or theoretical explanation, of how you would apply your employee-run business model to a mcdonald's, wal-mart, a hospital or jpmorgan chase?" >> well, the answer is best given not as a hypothetical but to describe an enterprise which is large like all of those are, which has done this. >> there's a film called "shift change," about the cooperative efforts. and we'll provide a link to that. >> well, the example i'm going to give is a company in spain. it's called mondragon, the mondragon cooperative corporation. and a little history may interest folks. it was started in the middle of

5:48 am

the 1950s by a catholic priest in the north of spain in the basque area just south of the pyrenees mountains. it was a time of terrible privation in spain after the world war ii and the spanish civil war. there was terrible unemployment in this area and the catholic priest decided that one way to deal with unemployment was not to wait for a capitalist employer to come in and hire people but to set up cooperatives. and he began with six parishioners in his roman catholic church to start a co-op. okay, this is 1956. let's fast forward to 2013. that corporation now has over 100,000 employees. it has been a success story of gargantuan proportions. it is a family of co-ops, within this large corporation. in most of these co-ops the workers make the decisions of how this cooperative works. so let me give you an idea of how successful they've been. they partner with microsoft and

5:49 am

general motors in their research labs because microsoft and general motors want to tap into their creative way of running a business. they have a rule that nobody can get more than six times what the lowest paid worker in an enterprise gets. the typical situation in a major american corporation is that the top executives gets 300 or 400 times what their lowest paid worker does. so they have solved the equality problem in a dramatic way for 120, roughly, thousand people. there's a concrete example of how you can make a cooperative democratically run enterprise successful, growing and becoming a powerful community force. there is arizmendi, the name of that priest in spain, there's the arizmendi bakeries, six of them in the bay area that are all run as cooperatives. and

5:50 am

they run it as a worker-directed enterprise. they've been very successful. their commitment, number one, is not profit. their commitment, number one, is not growth. their commitment, number one, is to their people. >> which brings me to a question from another viewer. how do you move to this alternative you're talking about and writing about without strong unions? union membership is down to its lowest level since 1936 when franklin roosevelt was president. and can you do this without increased strength among unions? >> a union in its negotiations with an employer currently is limited in most cases to asking for better wages, better working conditions. imagine with me for a moment what it would mean if the unions developed a new strategy. let's call it a two-track strategy. on the one hand you continue bargaining with your workers for better conditions from your

5:51 am

employer. but on the other hand you do something else. you begin to train workers to become able to run their own enterprises and to have a whole new bargaining chip when you confront an employer. many unions over the last 30 years have been confronted by a company that basically comes and says the following. we're thinking of leaving cincinnati, sheboygan, detroit, whatever. we need to get some concessions from you. we won't leave if you give us wage give backs, lower benefits, all the usual things, or else we'll leave. the union doesn't know what to do, is terrified, doesn't want to call the bluff because not sure it is a bluff, et cetera, et cetera, so eventually the union caves. that has been the history over and over again. imagine a union that had been able to say to these folks, okay, if you leave rather than coming to a reasonable accommodation with us, we are going to set up an enterprise right here. the factory you leave we will occupy. the jobs you don't pay us to do

5:52 am

we will do for ourselves. and you will be located in china bringing goods back here, but we'll continue to produce goods here and let's see which goods the american working people will buy. >> but they will need capital to do that. >> yes. and the question is where would the capital come from? >> the question is where will the capital come from? >> good. the answer is, where the capital come from, there are several possibilities. the first possibility is the united states government. the united states government has the money, needs to do something for our unemployment problem and here's a way to do it because as the marcora law in italy that i mentioned earlier illustrates there's a governmental and a social interest in doing this. this is a better way to solve the unemployment problem than giving people a dole for months or years at a time during which time they lose their job connections, they often lose their skills. this is a much better solution, giving them the startup money to

5:53 am

begin small, medium size enterprises that they will have a great interest in making successful because it's their future, it's their wellbeing that's at stake and it's their collectively owned and operated enterprise. well, why in the world don't we have a cooperative business administration providing startup money and technical help so that these kinds of enterprise, particularly helping unemployed people, could begin not only to help them and to help our economy but again to provide that freedom of choice for americans so we can all see how these enterprises work and make a collective decision whether we'd rather have an economy more of them than of the old capitalist type. and again i think that the capitalists would be surprised by how many of us would choose that other route. and that would be a way to get it going. >> this is all very provocative and very controversial. and very imaginative. we'll have you back at this table before the season is over.

5:54 am

but in the meantime i look forward to our live chat on billmoyers.com this coming tuesday at 1:00 pm eastern time. >> good. i look forward to it as well. >> so make a note, richard wolff will be responding to you directly, without the middleman, in a live chat at our website, billmoyers.com. you can start submitting your questions now at the website or on our facebook page. again, tuesday, march 26th, 1:00 p.m. eastern time. meanwhile, to mark the 10th anniversary of the u.s. invasion of iraq, fought at a cost that continues to mount, you can go to our website for a link to our much-discussed documentary, buying the war.

5:55 am

that's at billmoyers.com. i'll see you there and i'll see that's at billmoyers.com. i'll see you there and i'll see you here, next time. -- captions by vitac -- www.vitac.com don't wait a week to get more moyers. visit billmoyers.com for exclusive blogs, else cays, and video features. this episode is available on dvd for $19.95. tord or order, write to the add on your screen. funding it provided by carnegie corporation of new york, celebrating 100 years of philanthropy and committed to doing real and permanent good in the world.

5:56 am

the coleberg foundation. independent production fund with support from the partridge foundation, a john and paulie guth charitable fund. the clements foundation. park foundation, dedicated to heightening public awareness of critical issues. the herb alpert foundation, supporting organizations whose mission is to promote passion and creativity in our society. the bernard and audrey rappaport foundation. the betsy and jesse fink foundation, the hkh foundation, barbara g. fleischmann and mutual of america, designing customized, individual, and group retirement products. that's why we're your retirement company.

513 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

KQEH (PBS) (KQED Plus) Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service  The Chin Grimes TV News Archive

The Chin Grimes TV News Archive

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11